If you were wrongfully terminated from a civil service position within your local government, you might be eligible to receive some compensation for your trouble. For example, say you are placed on suspension and are on track to be terminated. However, you later appeal that decision, and your suspension and termination are lifted. As a result, you may be allowed to reclaim back pay and exceptional pay for the time you were prohibited from working. The following case out of Plaquemines parish discusses the issues of back pay and exceptional pay and how they apply within a court proceeding.

If you were wrongfully terminated from a civil service position within your local government, you might be eligible to receive some compensation for your trouble. For example, say you are placed on suspension and are on track to be terminated. However, you later appeal that decision, and your suspension and termination are lifted. As a result, you may be allowed to reclaim back pay and exceptional pay for the time you were prohibited from working. The following case out of Plaquemines parish discusses the issues of back pay and exceptional pay and how they apply within a court proceeding.

Loukisha A. Daisy applied for the position of Chief Internal Auditor at the Plaquemines Parish Government (PPG). Daisy was accepted on the condition that she complete all required courses and possess a CPA within one year of her hire date. Daisy worked for PPG for one year but did not obtain her CPA certification within that timeline. PPG moved to terminate her employment for this failure as well as two other non-critical mistakes on her part. Daisy was suspended until she had a predetermination hearing. After the suspension, Daisy was terminated.

Daisy appealed her termination to the Plaquemines Parish Civil Service Commission. The Commission reinstated her to her previous position but failed to award all of the back pay she sought in her initial appeal. Therefore, she appealed the Commission’s decision to the Louisiana Fourth Circuit court of appeals.

Insurance Dispute Lawyer Blog

Insurance Dispute Lawyer Blog

Workers’ compensation is a financial support system that may be available to injured employees. It aims to ensure employees are compensated for their injuries and do not bear the entire expenses of medical bills. Workers’ compensation laws differ from state to state. Still, the general idea is that employees can get benefits regardless of who was at fault for the injury so long as the injury arose from an act during employment.

Workers’ compensation is a financial support system that may be available to injured employees. It aims to ensure employees are compensated for their injuries and do not bear the entire expenses of medical bills. Workers’ compensation laws differ from state to state. Still, the general idea is that employees can get benefits regardless of who was at fault for the injury so long as the injury arose from an act during employment.  If you feel you have been wrongfully terminated, you might think it is sufficient to file a lawsuit accusing your former employer of violating the law. However, merely making legal accusations is insufficient. To survive a motion to dismiss, you must include sufficient factual details to support your claims against your former employer. The case shown below demonstrates these principles.

If you feel you have been wrongfully terminated, you might think it is sufficient to file a lawsuit accusing your former employer of violating the law. However, merely making legal accusations is insufficient. To survive a motion to dismiss, you must include sufficient factual details to support your claims against your former employer. The case shown below demonstrates these principles. When finding yourself as a defendant in a lawsuit, you will want to limit your liability as much as possible. Your liability could be altered when a co-defendant is found to be at fault for the injuries to a certain extent. However, when one defendant is dismissed before the trial begins, can another defendant seeking to split the fault appeal the decision? A case arising out of St. Charles Parish aims to answer this question.

When finding yourself as a defendant in a lawsuit, you will want to limit your liability as much as possible. Your liability could be altered when a co-defendant is found to be at fault for the injuries to a certain extent. However, when one defendant is dismissed before the trial begins, can another defendant seeking to split the fault appeal the decision? A case arising out of St. Charles Parish aims to answer this question. Driving poses undeniable risks. However, travelers may need to consider how unsafe a barrier curb may be in certain situations. When is the state liable for these conditions? A case from the St. John Baptist parish considered how the state department of development and transportation was at fault for construction risks that contributed to an accident.

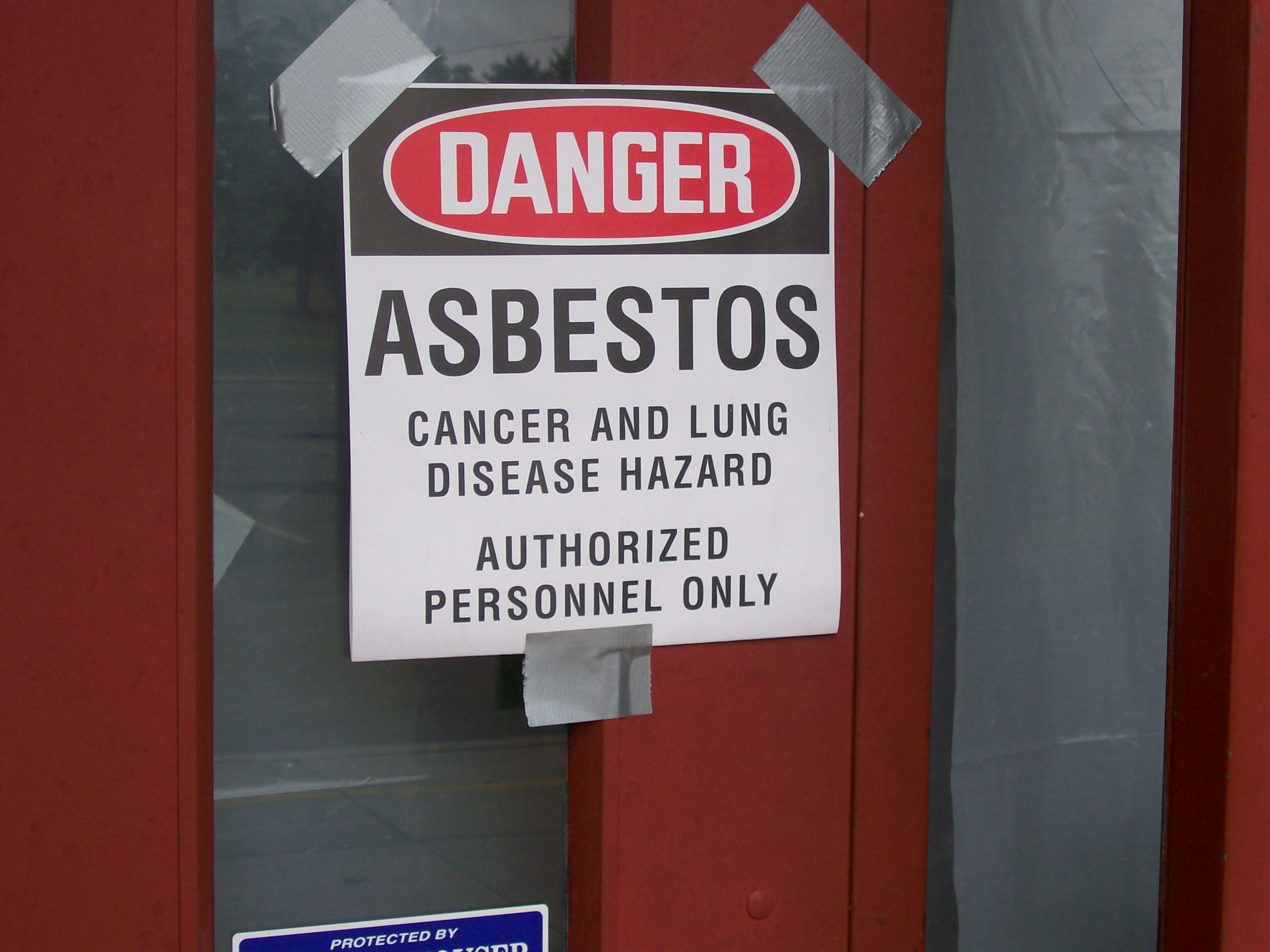

Driving poses undeniable risks. However, travelers may need to consider how unsafe a barrier curb may be in certain situations. When is the state liable for these conditions? A case from the St. John Baptist parish considered how the state department of development and transportation was at fault for construction risks that contributed to an accident.  Risks are involved with many jobs. While employees may take risks at work, knowingly or unknowingly, one does not usually expect to put their family at risk while on the job. Jimmy Williams Sr found himself in this situation when his exposure to asbestos at work impacted his wife’s health through her handling his work clothes.

Risks are involved with many jobs. While employees may take risks at work, knowingly or unknowingly, one does not usually expect to put their family at risk while on the job. Jimmy Williams Sr found himself in this situation when his exposure to asbestos at work impacted his wife’s health through her handling his work clothes.  In Louisiana, a conspiracy is a combination of two or more persons to do something unlawful, either as a means or as an ultimate end. Once a conspiracy has been established, an act done by one in the furtherance of the unlawful act is, by law, the act of all others involved in the conspiracy.

In Louisiana, a conspiracy is a combination of two or more persons to do something unlawful, either as a means or as an ultimate end. Once a conspiracy has been established, an act done by one in the furtherance of the unlawful act is, by law, the act of all others involved in the conspiracy.  Rick Sheppard, an inmate in the custody of the

Rick Sheppard, an inmate in the custody of the  A man is in the hands of a facility tasked with providing sufficient medical care. Instead of meeting this standard of care and due diligence, the facility fails to adjust the man’s diet, and he chokes on solid food that he should not eat, leading to his death. When his parents and children bring multiple complaints of medical malpractice, his children’s claim gets dismissed despite the apparent negligence of the facility. Why did that happen?

A man is in the hands of a facility tasked with providing sufficient medical care. Instead of meeting this standard of care and due diligence, the facility fails to adjust the man’s diet, and he chokes on solid food that he should not eat, leading to his death. When his parents and children bring multiple complaints of medical malpractice, his children’s claim gets dismissed despite the apparent negligence of the facility. Why did that happen? Slip-and-fall cases are prevalent in the restaurant industry. In handling various kinds of food and drink, it makes sense that sometimes, things end up on the floor and can cause a slip hazard for customers. But when a customer falls without a clear cause, how can the court determine who is at fault?

Slip-and-fall cases are prevalent in the restaurant industry. In handling various kinds of food and drink, it makes sense that sometimes, things end up on the floor and can cause a slip hazard for customers. But when a customer falls without a clear cause, how can the court determine who is at fault?